The commonest chemotherapy regimen in lymphoma medicine by far is CHOP. This is an odd acronym and takes some explanation. The drugs included are Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin (this is the red drug and is otherwise called Hydroxydaunorubicin, hence the 'H'), Vincristine (which comes from the Madagascan Periwinkle hence the vinca plant symbol for Lymphoma Action - otherwise known as Oncovin, giving the 'O') and Prednisolone.

CHOP exemplifies the principles behind combination chemotherapy. Imagine the days before combination chemotherapy, sitting down in a bar with some colleagues trying to work out which drugs to put together. The following principles are helpful to guide the final result:

- each individual drug should be active in the disease of interest

- the mechanism of action (and therefore of resistance) of each agent should be distinct

- each agent should work at a different part of the cell cycle

- each agent should have distinct (and preferably non-overlapping) dose limiting toxicities enabling the delivery of each drug at near maximal dose

- the pharmacokinetics should not interfere too much with each other

The table below demonstrates how CHOP (combined with rituximab) exemplifies this approach. Under toxicity, 'Myelo' means myelosuppression i.e. low bloods counts (neutropenia etc) and DLT stands for dose-limiting toxicity. You'll note that some of the drugs are cell cycle non-specific which means they act on cancer cells irrespective of whether they are actively cycling or not. Since in any given cancer, usually a minority of cells are actively cycling (high grade lymphoma often being an exception to this rule), including a cycle non-specific drug in a regimen is highly desirable.

|

Drug

|

Action

|

Cell cycle

|

Toxicity

|

|

Rituximab

|

Anti-CD20 mAb

|

Cycle

non-specific

|

No

DLT

|

|

Cyclophosphamide

|

Alkylating agent

|

Cycle non-specific

|

Myelo

(also bladder)

|

|

Doxorubicin

|

Intercalates DNA

|

S-phase

|

Myelo (also heart)

|

|

Vincristine

|

Anti-metabolite

|

M-phase

|

Neuropathy

|

|

Prednisolone

|

glucocorticoid

|

G1

phase

|

Metabolic / neurol

|

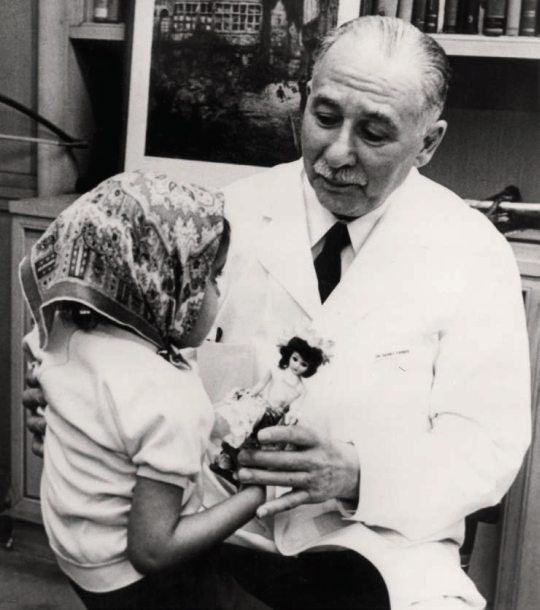

CHOP was initially used for high grade non-Hodgkin Lymphomas. This was in the era before pathologists had immunohistochemistry, so physicians were blind to whether they were treating B-cell or T-cell NHL. With the advent of immunostaining, and then with therapeutic monoclonal antibodies, rituximab was added to the CHOP regimen in high grade B-cell lymphoma (initially diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, the commonest subtype). Results were dramatic with a notable prolongation not just in remission lengths, but also in overall survival. This was first demonstrated by Coiffier et al (who sadly recently passed away) in patients aged 60-80.

|

| Prof B Coiffer |

He performed a randomised study comparing 8 cycles of CHOP with 8 cycles of R-CHOP. Long term follow up of this study is shown graphically below and is taken from Coiffier et al (2010) Blood. The 10 year overall survival rose from 27% to 43% - a massive 16% absolute increase. Since then, adding rituximab to this regimen has cured 1000s of people of their diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

|

| Overall survival with 10 years of follow up |

CHOP and R-CHOP also have what physicians often describe as an acceptable safety profile. Of course it is really up to the patient to say whether the side effects are 'acceptable' or not. But generally what is meant by this is that it is delivered as an out patient, it is safely given to patients even as they get older (certainly up to 80 years of age) and patients mostly report that the side effects improve with time after finishing. Common side effects include:

- Infusional reactions due to the rituximab (this is quite common but usually only happens with the first dose; subsequent doses are often much less affected.

- Fatigue: a common complaint, often under-estimated by doctors and for which we can do very little. Sometimes this can also be prolonged, interfering with recovery after chemotherapy.

- Hair loss: due largely to the doxorubicin, this is pretty much invariable although it does grow back afterwards (and is frequently different from before - sometimes curly and sometimes even a different colour!)

- Neuropathy: due to the vincristine. Symptoms are usually mild with numbness and tingling in the finger and toes. If it gets worse (starting to interfere with function) then the dose should be reduced. Usually it does recover although not always completely and it can take up to 2 years to get the most recovery. Beware giving vincristine to someone with foot drop as this could be an indication of an underlying hereditary neuropathy which maybe dramatically unmasked when this drug is administered!

- Heart damage: due to the doxorubicin. This is less common but is probably underestimated. 6 courses gives a cumulative dose of doxorubicin of 300mg/m2 which probably increases the risk of heart failure over the years by several fold.

- Infection risk: the 2nd of the 3 weeks in a cycle is usually characterised by neutropenia. Neutropenic fever (which is medical emergency) happens in about 15-20% of patients on R-CHOP and usually necessitates hospital admission. This frequency can be reduced by the use of G-CSF injections and prophylactic antibiotics.

- Nausea: thankfully we have excellent anti-sickness drugs now so debilitating nausea is uncommon.

- Taste change: this is common although the mechanism isn't clear. Patients often describe a metallic taste and they can go off foods which they previously enjoyed such as curry or coffee. It usually does reverse at the end of treatment but it can take some time.

- Mood changes and raised blood sugars due to the prednisolone. It is important to tell diabetics to monitor their blood sugars more closely and they may need to alter their anti-diabetic medication when on R-CHOP.

There are numerous other side effects reported, but these are the main ones and the ones I discuss with patients. I also explain that there is a small risk of dying on chemotherapy, but R-CHOP is generally considered a safe chemotherapy and the risk is 1% or less for most people. Certain groups do have a higher risk though, such as the elderly, and those who have had a previous organ transplant. The cause of death is often infection and it's often when people haven't told us they are unwell with a fever, so contacting the medical team for advice quickly is important when on chemotherapy.

R-CHOP is generally given once every 3 weeks. Before the introduction of rituximab, the German High Grade Lymphoma study group found that administering CHOP every 14 days was a little more effective. In oder to deliver this schedule, they had to routinely give all patients GCSF injections and also additional preventative antibiotics (against an infection called PCP). Once rituximab was introduced it was controversial whether there was any benefit with the 14 day administration. This issue was largely settled by a UK study comparing R-CHOP given every 21 days with every 14 days. The study was led by Professor Cunningham of the Royal Marsden in London and showed equivalent outcomes. This is illustrated by the graph below taken from Cunningham et al (2013) Lancet.

R-CHOP-21 therefore has remained standard of care. Many attempts to better R-CHOP have been made and have largely failed - but I will blog about that in a subsequent post.

For now, R-CHOP in my view is the King of Chemo, exemplifying the principles of combination chemotherapy, resulting in excellent outcomes for the majority of patients with high grade B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas and all with side effects which, although sometimes severe, are generally tolerable. Of course R-CHOP isn't right for everybody but it remains the gold standard regimen world wide for most with the commonest forms of lymphoma. As I say to my trainees - if someone asks you how to treat someone with lymphoma, you'll not usually be too far wrong saying R-CHOP-21.